Beyond FOCUS-PDCA: Why It’s Time to Take the Next Step

by Charles Mount and Dan Chauncey

Hospitals have long utilized the tools and methodologies of FOCUS-PDCA for Performance Improvement. Hospital Corporation of America (HCA) adapted Deming’s PDCA and added the FOCUS portion specifically to help hospitals identify their inefficient or troublesome areas (Caldwell 1998). This was started in the late 1980’s and has been expanded across the entire industry over the past 20 years. However, is the traditional FOCUS-PDCA sufficient to truly solve today’s healthcare problems transform the industry?

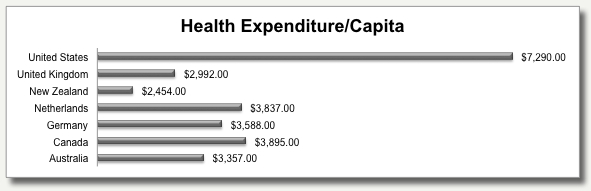

While the United States has the most costly healthcare system in the world, it ranks poorly in comparison to other countries. In a comparison to six other industrialized countries (Australia, Canada, Germany, the Netherlands, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom), the U.S. ranked near the bottom in five performance dimensions:

- quality

- access

- efficiency

- equity

- productive lives

As shown in figure 1, per capita expenditures in the U.S. far exceed the other countries (Davis, Schoen and Stremikis 2010).

Figure 1. Health expenditure per capita for seven nations.

And even more worrisome, the trend continues across the five performance dimensions. As shown in figure 2, the U.S. ranks last or next to last in all five dimensions. These rankings have been consistent in the 2004, 2006, 2007 and 2010 rankings (Davis, Schoen and Stremikis 2010).

Figure 2. Rankings of nations on five performance dimensions.

FOCUS-PDCA continues to be used by many hospitals as their primary Performance Improvement approach to meet the requirements of the Joint Commission for their three-year accreditations. The Joint Commission's mission is to improve the safety and quality of care provided to the public through the provision of health care accreditation and related services that support performance improvement in health care organizations (Hermann 2002). While the Joint Commission doesn’t mandate which methodology is utilized, it has selected Lean and Six Sigma as the methodologies to improve its own internal processes. Joint Commission president, Dr. Mark Chassin is a certified Lean Six Sigma practitioner (Adrian 2009). Historically, FOCUS-PDCA has shown some degree of success in improving healthcare processes. Still, most of these successes are reactive in nature and do not generally improve financial results. FOCUS-PDCA does not provide for the breakthroughs for which an Integrated approach to Performance Improvement is ideally suited. In essence, it may no longer be sufficient. As an example, at Seattle Children’s Hospital, staff would stockpile supplies. A nurse in the Intensive Care Unit was concerned about having the tools she needed for her patients that she began stashing them away. This created supply chain issues which actually resulted in even more shortages (Weed 2010). This is the type of problem that is not normally addressed by FOCUS-PDCA.

Historically, FOCUS-PDCA has shown some degree of success in improving healthcare processes. Still, most of these successes are reactive in nature and do not generally improve financial results. FOCUS-PDCA does not provide for the breakthroughs for which an Integrated approach to Performance Improvement is ideally suited. In essence, it may no longer be sufficient. As an example, at Seattle Children’s Hospital, staff would stockpile supplies. A nurse in the Intensive Care Unit was concerned about having the tools she needed for her patients that she began stashing them away. This created supply chain issues which actually resulted in even more shortages (Weed 2010). This is the type of problem that is not normally addressed by FOCUS-PDCA.

Today’s healthcare processes involve extensively broken or misplaced steps with multiple handoffs, too many decision points, and a host of process constraints (bottlenecks). If they can be resolved with traditional FOCUS-PDCA, then all is well and done. Typically, however, all is not well. For so many of today's hospitals, the improvements are often short-lived and require endless rework. Deming saw this situation repeated over and over again across many industries. He cautioned against reaching for the quick fix or fast band-aid but to walk through the entire process (Deming 1986). The primary fault lies not with the hospital staff - quite frankly no individual or group of people is at fault. Where the difficulty lies is in the "sustainability" of the improvements themselves.

Byrnes and Fifer state that "a quiet revolution" is taking place that places quality improvement—performance improvement—as the link between better outcomes (patient safety and delivery of care) and lower costs. This revolution includes the allocation of resources for quality programs and executive leadership teams are discussing quality at their operational meetings (Byrnes and Fifer 2010).

Despite this increased level of activity in performance improvement, the improvements are not being sustained. According to Michael Porter in Redefining Health Care, there are at least three reasons why process improvements are rarely sustained (Porter 2006):

- Time pressures create desire for fast solutions.

- Attention spans are short and easily overcome by tomorrow's priorities.

- Problems cut across multiple departments with no single owner of the process.

What is needed, then, is a methodology that is sufficient enough to achieve true sustainment. It must be robust, involve disciplined thinking and focus heavily on data. It must be, therefore, strong enough to break through healthcare’s “hidden factory” (figure 3) and uncover the true cost of poor quality.

Figure 3. Healthcare's hidden factory.

What lies above the waterline in the "iceberg" illustration is where much of the day-to-day performance improvements are focused:

- Inventory difficulties

- Defects and errors

- Endless Inspections

- Costly rework

What lies below the waterline are all the issues that prevent processes from being permanently resolved, including such items as long cycle times, unused capacity, planning delays, excessive employee turnover, etc. Because they are below the water surface, and thus "hidden" they exhibit five difficult-to-resolve characteristics:

- Murky and therefore difficult to see easily.

- Deep and complex, requiring advanced tools.

- Stuck like the "muck" of a river bed and difficult to extract.

- Rarely if ever come to the surface to easy analysis.

- Loaded with multiple other problems and difficult to break apart into bite size chunks

FOCUS-PDCA has not shown that it is capable of breaking through the hidden factory. A reactive approach only works sporadically and result in less than optimal long term limited sustainability. An integrated performance improvement approach has sufficient rigor to accurately assess the issues below the water line and raise the dangerous and most inefficient or costly processes to the surface where they can be resolved. Without a structured and rigorous performance improvement program that is supported by the executive leadership team, many broken healthcare processes remain broken. Occasionally they rise to the surface for a fast fix, only to sink back down into the muck of the hidden factory.

For example, trying to improve patient flow in the Emergency Department can be a daunting undertaking. There are multiple departments, a host of physicians, nurses, technicians and clerks involved and endless resources required to manage the flow. In such a complex system, quality and cost issues are sure to be present. When they do arise, time constraints tend to result in quick fixes instead of more sustainable solutions that address root causes by implementing fundamental changes to the process. Initially, the issue appears to be resolved, the flow of patients improves or the quality issue seems to be fixed. However, the quick fix unravels; the patient flow reverts back to its original state or the same quality issue resurfaces.

True sustainment requires a permanent fix—a fundamental change to the underlying process. That is the weakness of FOCUS-PDCA as it has evolved in healthcare today. While the underlying theory does provide for the requisite rigor, it lacks a documented application process as well as specific application of the tools necessary to drive both quality and financial improvements at both the process and the enterprise levels.

A focused performance improvement program that applies the right tool to the right problem, at the right time works! Ask the physicians and nurses who have tried it; ask the patients who have experienced it (Graban 2009).

The move to improve the quality and cost effectiveness is gaining momentum. Healthcare reform is being widely debated regarding its efficacy in its current form/approach. Edmund says that quality and patient safety advocates say that it will help improve quality of care, delivery or care, and patient safety (Edmund 2010). While Edmund's comments do not specifically address costs, leadership must recognize that quality must improve, and so must the financial results for healthcare organizations to keep their doors open!

Also in This Issue of the Newsletter

Webinar Spotlight: Medication Reconciliation: A Big Pill to Swallow, October 6th @ 1 PM ET. Click here to register.

The 10 Most Common Performance Improvement Mistakes, Part 4: Boil the Ocean

Works Cited

Adrian, Nicole. "Don't Just Talk the Talk." Quality Progress, July 2009: 31-33.

ASQ Lean Six Sigma Hospital Study Advisory Committee. "Get Your Checkup." Quality Progress, August 2009: 44-50.

Byrnes, John, and Joe Fifer. "Moving Quality to the top of the Hospital Agenda." Healthcare Financial Management, August 2010: 64-69.

Caldwell, Chip. The Handbook for Managing Change in Healthcare. Milwaukee: ASQ Quality Press, 1998.

Davis, Karen, Cathy Schoen, and Kristof Stremikis. Mirror, Mirror on the Wall: How the Performance of the U.S. Healthcare System Compares Internationally. Annual Update, Commonwealth Fund, 2010.

Deming, W. Edwards. Out of the Crisis. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 1986.

Edmund, Mark. "Quality Key Ingrediant in Healthcare Reform." ASQ Quality Progress Website. www.qualityprogress.com (accessed 2010).

Graban, Mark. Lean Hospitals. New York: Productivity Press, 2009.

Hermann, Kenneth G. "The Healthcare System - Strategies for Improvement - A Joint Commission Perspective." ASQ Meeting May 21, 2002, Healthcare Division Track. Denver: American Society for Quality, 2002.

Knight, Alex. "Healing the National Health Service." The Ashridge Journal, Winter 2000/01: 8-15.

Porter, Michael E. Redefining Health Care. Boston : Harvard Business School Press, 2006.

Weed, Julie. "Factory Efficiency Comes to the Hospital." New York Times, July 9, 2010.

Follow Us: